Modeling vs Diagramming: Why the Best Teams Do Both

Modeling tools are the gym memberships of enterprise software. Everyone buys them. Nobody uses them.

Meanwhile, the diagramming crowd has the opposite problem: everyone draws, but six months later you're drowning in contradictory boxes scattered across Confluence.

The modeling camp says diagrams are just pretty pictures — without structure, without relationships, without a proper metamodel, you're just drawing boxes that will rot. The diagramming camp says models are overkill — nobody wants to learn a new tool, maintain a repository, or fill out 15 fields just to document a service.

Here's the thing: they're both right. And they're both wrong.

The answer isn't modeling or diagramming. It's knowing when each approach works — and finding the mix that actually sticks for your software architecture documentation.

What's the Difference?

A diagram is a picture. You draw boxes, connect them with lines, and you're done. The boxes don't "know" about each other — they're just shapes on a canvas.

A model is a structured representation. Each component has an identity. Relationships are explicit and queryable. When you draw the same service on two different diagrams, it's the same underlying object — change it once, and both diagrams update.

Think of it like the difference between a photo of your org chart and an actual HR system. One is a snapshot; the other is a source of truth.

The Case for Modeling

Let's give modeling its due.

When you model your architecture — when components have identities, relationships are explicit, and changes propagate across views — you get real benefits:

Consistency across views. Change a service name once, and it updates everywhere. No hunting through 47 diagrams wondering which ones are stale.

Impact analysis. "What depends on the Payment Service?" becomes a query, not a guessing game.

Living documentation. A model can be queried, validated, compared over time. It's not just a snapshot — it's a source of truth.

Better onboarding. New team members can explore the architecture. They're not decoding someone's personal Visio style.

For complex systems, for regulated industries, for teams that need to answer hard questions about their architecture — modeling matters. (For practical guidance, see our C4 modeling tips.)

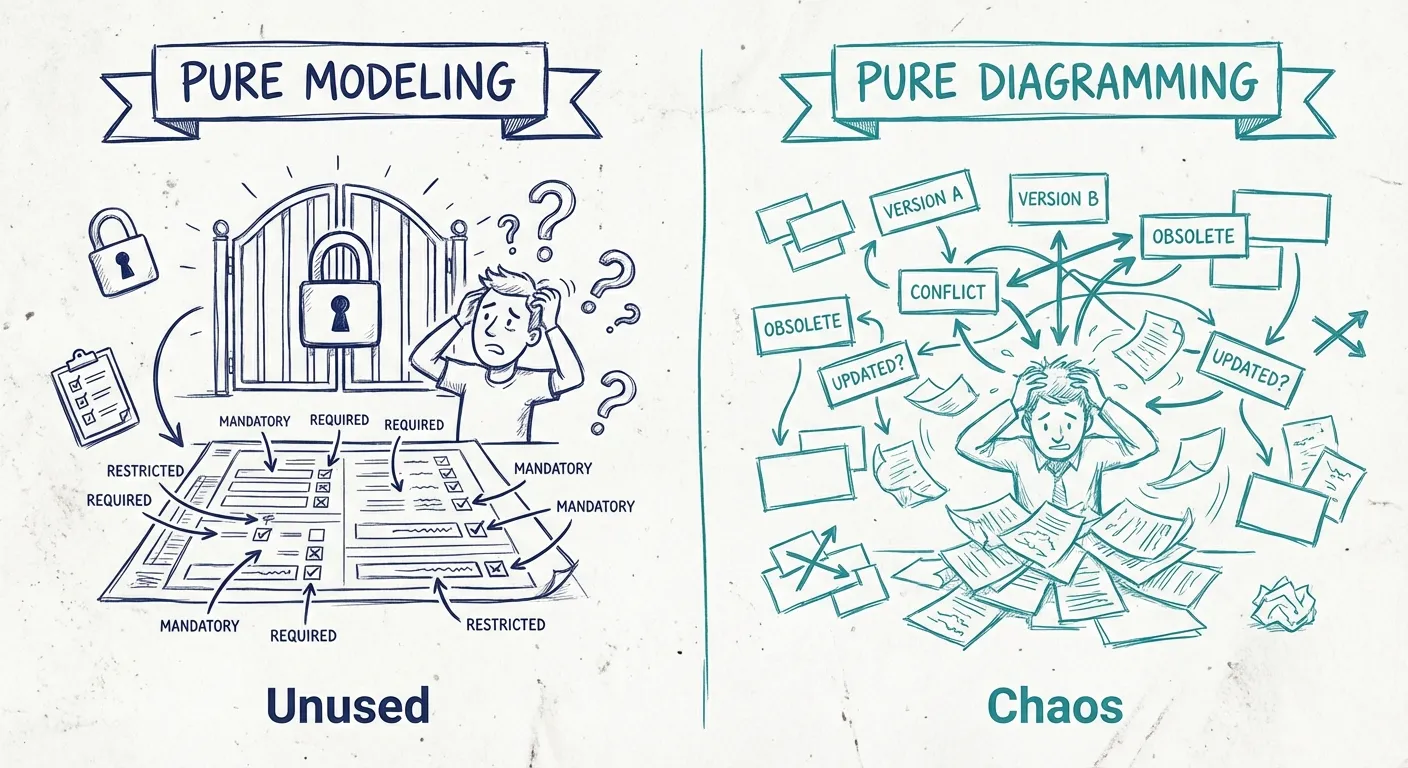

Why Pure Modeling Often Fails

So if modeling is so great, why don't more teams do it?

Because adoption is brutal.

Most modeling tools were built for enterprise architects, not developers. They come with:

- Mandatory metadata fields

- Rigid metamodels

- Certification requirements

- Learning curves measured in weeks

Try telling a development team they need to "update the architecture repository" every time they add a service. You'll get compliance theater at best, open revolt at worst.

Modeling fails when it becomes a bottleneck. When only the "architecture team" can update the model. When developers work around it instead of with it.

The best model in the world is worthless if nobody uses it. (This is why heavyweight EA tools are often overkill for most teams.)

The Case for Diagramming

Diagrams have their own strengths.

Low barrier to entry. Anyone can draw a box. No training required.

Flexibility. Need to sketch an idea on a whiteboard? Explain a concept to a stakeholder? Diagrams adapt to the moment.

Speed. Sometimes you just need to communicate something now. Not after you've modeled it properly.

Developer buy-in. Developers will draw diagrams. They won't always fill out repository forms.

For brainstorming, for quick communication, for getting ideas out of heads and onto screens — diagrams win.

Why Pure Diagramming Also Fails

But we've all seen what happens when diagramming is the only approach.

Diagram sprawl. Fifty versions of "the architecture" scattered across Confluence, Miro, Google Slides, and that one guy's desktop.

No single source of truth. Which diagram is current? The one from last month's presentation? The whiteboard photo from the workshop?

Inconsistent notation. One person's "service" is another person's "component." Colors mean different things. Arrows are... decorative?

Documentation rot. Diagrams get created for a specific meeting, then never updated. Six months later, they're actively misleading.

No traceability. "What changed since last quarter?" Good luck diffing two PNGs.

Pure diagramming scales until it doesn't. And then you're drowning in boxes.

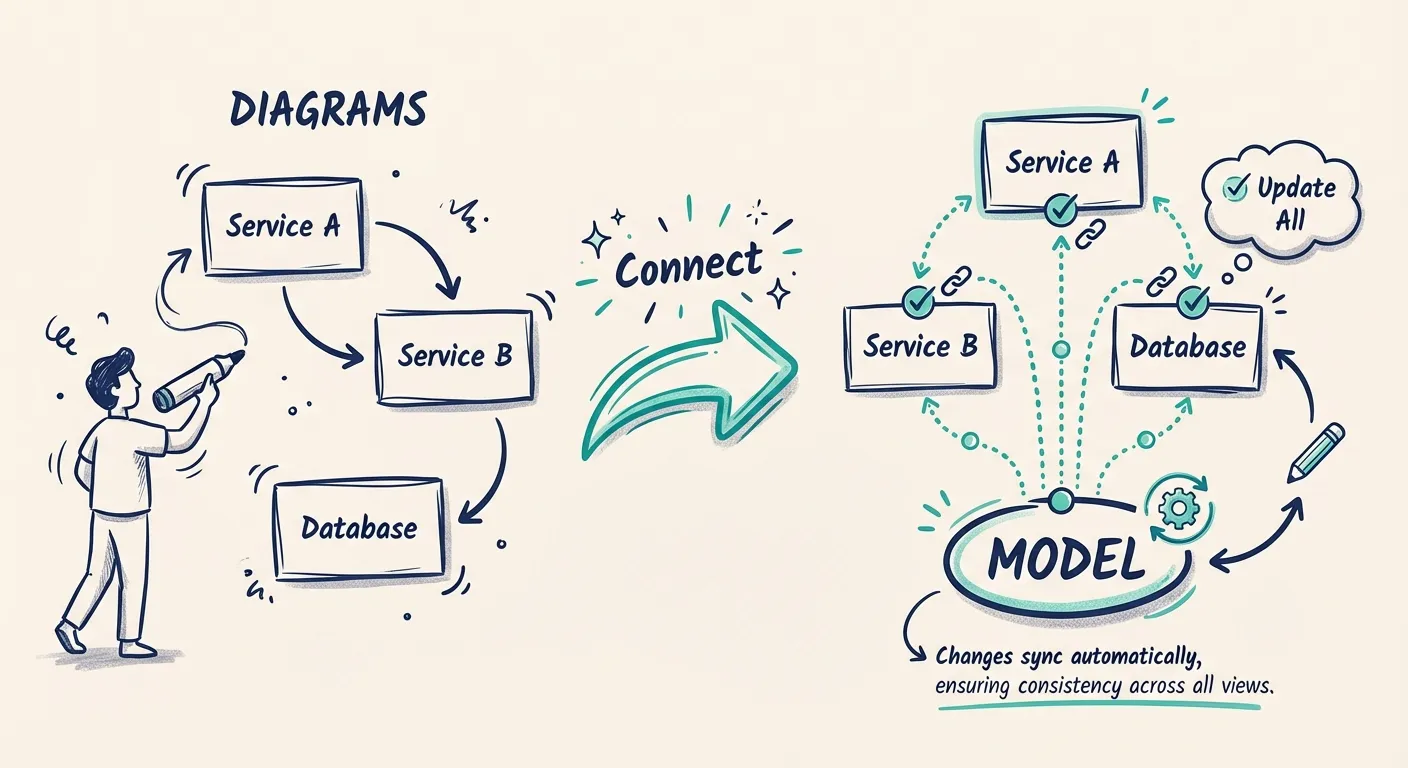

The Golden Mix

The teams that get this right don't choose between modeling and diagramming. They find the balance — a model-based documentation approach that still feels like drawing.

Here's what that looks like:

Start with diagrams, connect to a model

Let people draw. Don't force them into a modeling tool on day one. Capture the architecture in a way that feels natural.

But link those diagrams to shared components. When someone draws "Customer Service," it's not just a box — it's a reference to the real thing. Change it in one place, and all the diagrams reflect it.

Model the important stuff, don't model everything

You don't need to model every class, every function, every internal detail. Model the things that matter:

- Systems and their boundaries

- Key services and data stores

- Integrations and dependencies

Keep the model lightweight. If it's too heavy, people will route around it.

Make modeling feel like diagramming

The tooling matters. If updating the model requires switching to a different app, filling out forms, and waiting for approval — people won't do it.

The best architecture tools feel like drawing tools. You drag boxes, you connect arrows, and behind the scenes, you're building a model.

Let the model serve the diagrams

The model isn't the point. The understanding is the point.

Models should make it easier to create diagrams, not harder. Generate views. Highlight specific use cases. Show what changed.

If your model makes documentation harder, you're doing it wrong. (For tips on making your architecture diagrams clearer, see how to improve your C4 diagrams.)

What This Looks Like in Practice

Scenario 1: New developer onboarding

Instead of handing them a stale PDF, you give them an interactive architecture they can explore. Click on a service, see its dependencies. Zoom out for context, zoom in for detail.

That's modeling working for diagramming.

Scenario 2: Architecture review

Someone proposes a change. Instead of debating in the abstract, you pull up the current architecture, trace the dependencies, and see exactly what's affected.

That's modeling enabling impact analysis — while still looking like a diagram.

Scenario 3: Quick stakeholder explanation

A PM asks how the checkout flow works. You don't fire up the enterprise modeling tool. You show them a diagram — but it's generated from the model, so it's current.

That's the best of both worlds.

The right mix for your team depends on size (larger teams need more structure), system complexity (microservices sprawl needs modeling more than a monolith), stakeholder needs (regulated industries need traceability), and culture. Start where you are — if your team draws diagrams, don't rip that away. Augment it. Add structure gradually. Let modeling earn its place.

The Bottom Line

Modeling without diagrams is inaccessible. Diagramming without modeling is unsustainable.

The teams that win are the ones that stop treating this as either/or.

Draw when you need to communicate. Model when you need consistency. And find the tools that let you do both without switching contexts.

That's the golden mix.

You Might Also Like

Diagram as Code: When Text Wins, When It Doesn't, and What Comes Next

Diagram-as-code promises version control, diffs, and developer workflows. But it also trades visual thinking for syntax overhead. Here's an honest look at when text-based architecture works and when visual-first is better.

C4 Model vs UML: Which Should Your Team Actually Use?

UML has 14 diagram types. Most teams use two or three. The C4 model offers a pragmatic alternative: four levels of abstraction that developers actually want to maintain.

The Software Architecture Documentation Tool Your Team Will Actually Use

Most architecture documentation dies within weeks. The problem isn't discipline. It's tools built for a world that doesn't exist anymore. Here's what modern teams actually need.