C4 Model Use Cases: The Missing Layer Your Diagrams Need

You know C4. Context, Containers, Components, Code. Four levels of zoom.

But here's the thing: those diagrams don't tell you how your system actually works.

Your Container diagram shows an API Gateway, a Customer Service, and an Order Database. Fine. But when your new developer asks "what happens when a customer places an order?" — your static boxes don't answer that.

That's the gap. And it's why your architecture documentation feels incomplete even when you've drawn all the diagrams.

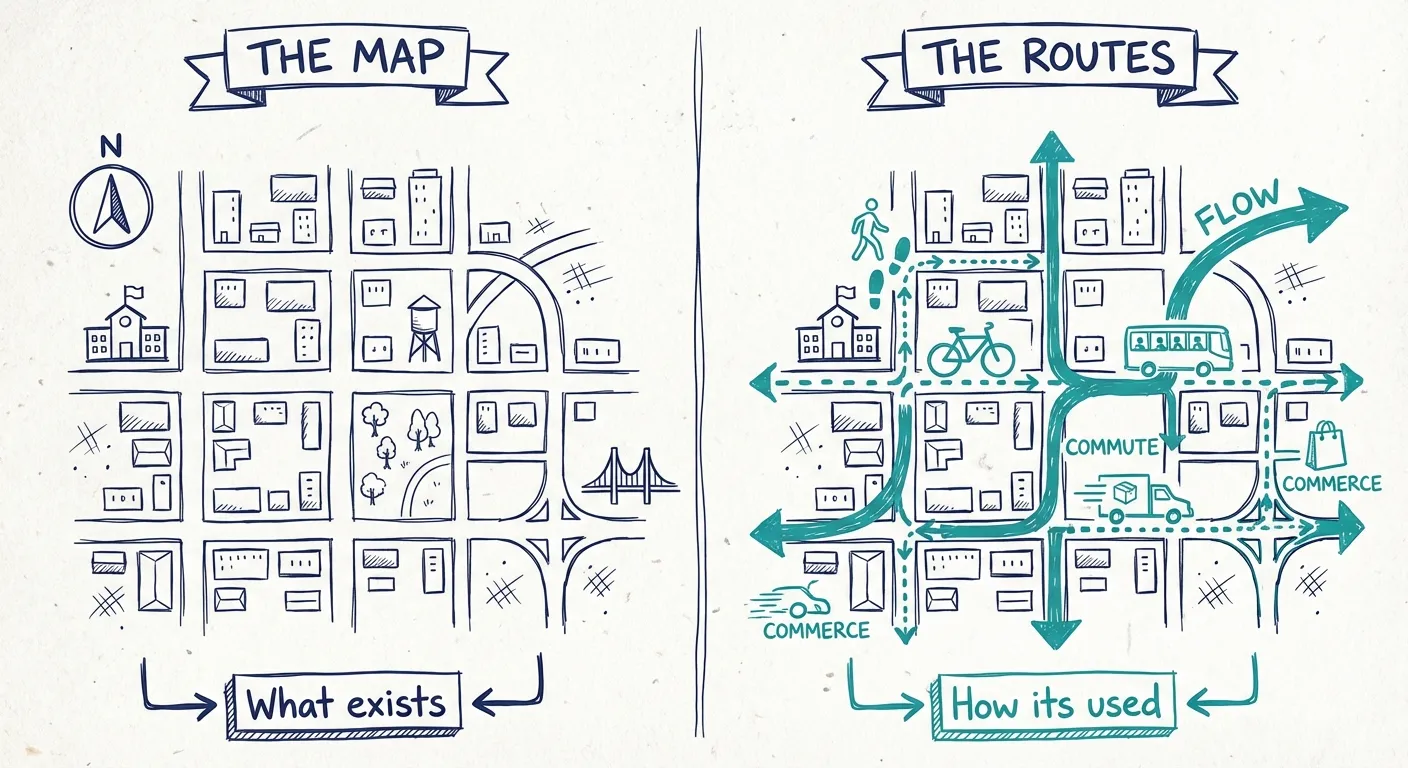

The Problem: Maps Without Routes

C4 gives you a snapshot of what exists. The structure. The boxes.

What it doesn't give you is behavior.

| Physical Architecture | Use Cases |

|---|---|

| What exists | How it's used |

| Servers, databases, services | Journeys, flows, scenarios |

| Static structure | Dynamic behavior |

| "The map" | "The routes people take" |

Think of it this way. Your architecture is a city. C4 gives you the map. But a map doesn't show you how people actually move through it. Which routes are busy? Where do requests flow during checkout?

Use cases are the routes.

Same Boxes, Different Stories

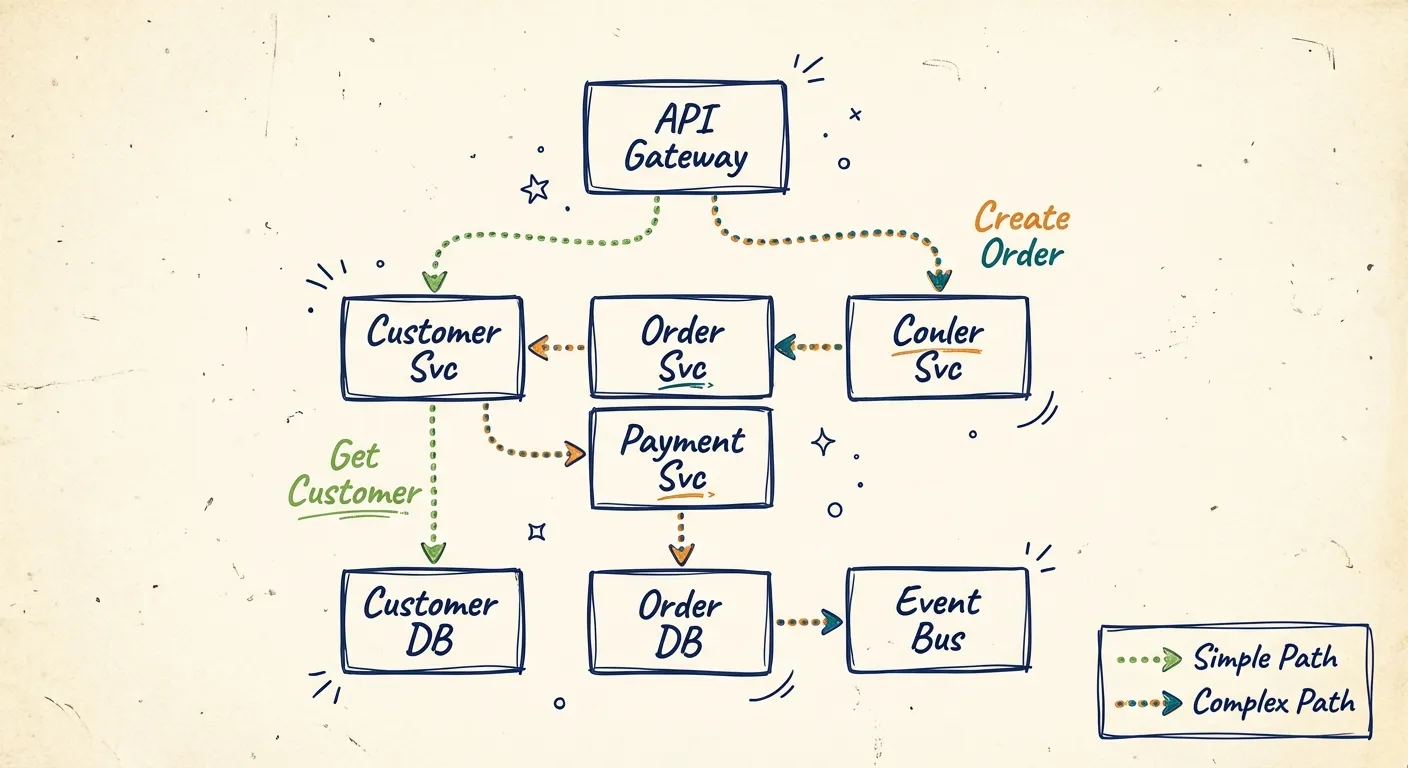

Take a typical e-commerce backend. Seven containers:

- API Gateway

- Customer Service

- Order Service

- Payment Service

- Customer Database

- Order Database

- Event Bus

That's the architecture. But this same architecture supports completely different paths:

Get Customer

API Gateway -> Customer Service -> Customer Database

Create Order

API Gateway -> Order Service -> Customer Service (verify) -> Payment Service -> Order Database -> Event Bus

Process Refund

API Gateway -> Order Service -> Payment Service -> Order Database -> Event Bus -> Customer Service (notify)

Same boxes. Different arrows. Different stories.

This is what "understanding your architecture" actually means. Not knowing what exists — knowing how it behaves.

Why This Matters More Than You Think

Static C4 diagrams leave you blind in the moments that count:

Onboarding. "Here are our services" teaches nothing. "Here's what happens when a customer checks out" — that's learnable.

Debugging. Something broke. First question: what path did this request take? Your Container diagram has no answer.

Impact analysis. Before you touch the Payment Service, you need to know which flows depend on it. Static boxes don't tell you.

Stakeholder communication. Business people don't think in containers. They think in use cases. "How does order processing work?" is a question they'll ask. "Walk me through your Container diagram" is not.

C4's Forgotten Feature

The C4 model actually includes dynamic diagrams. They're designed for exactly this — showing how components interact for a specific scenario.

Most teams never create them.

Why? They feel like extra work. They're disconnected from the main model. There's no clear guidance on when to bother.

So teams draw their Context and Container diagrams and call it done. The behavior lives in people's heads — or nowhere at all.

The Fix: Use Cases as a First-Class Layer

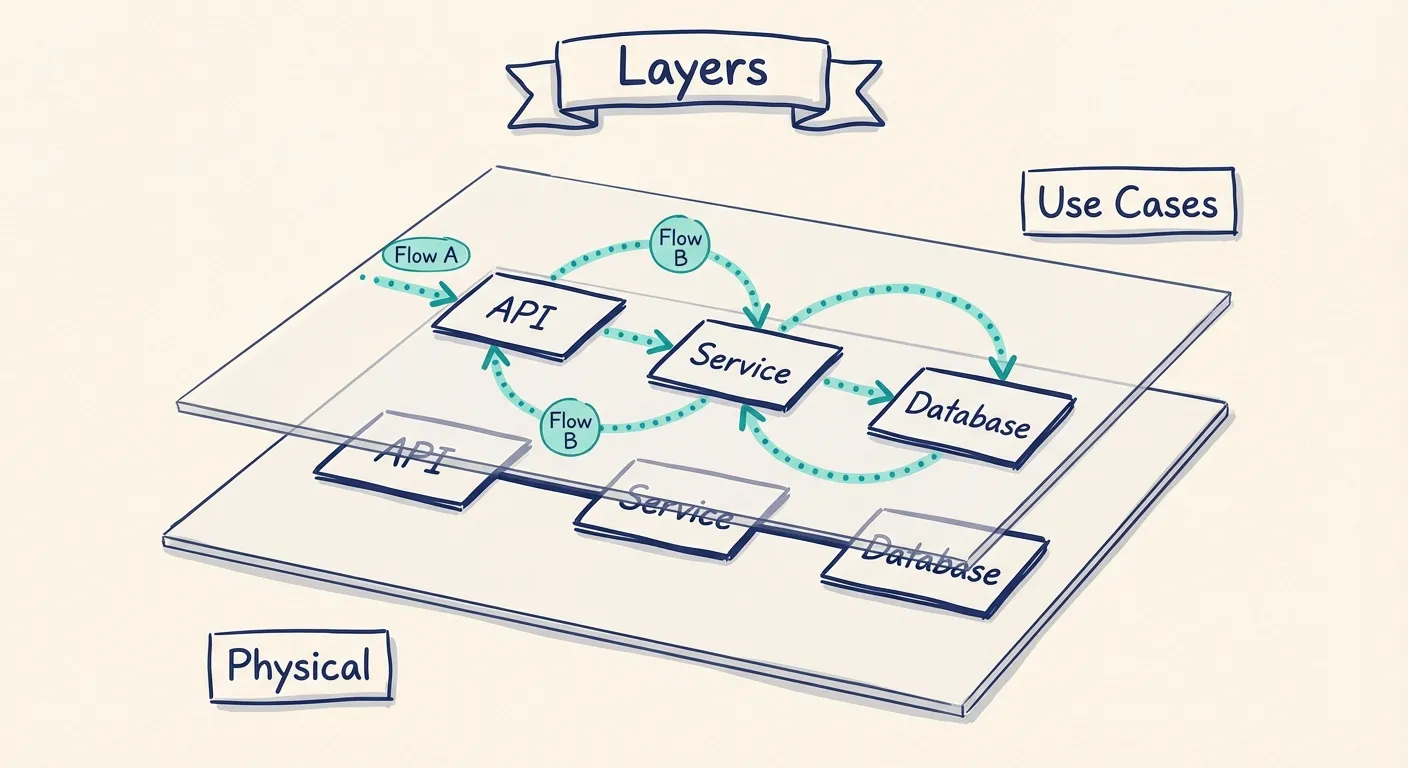

Here's what works: treat use cases as a layer on top of your C4 model, not a separate artifact.

Your physical architecture is the foundation. Model it once, keep it current.

Your use cases are overlays. Each one traces a path through the existing containers. Same boxes, different highlighted connections.

This gives you:

One model, many views. You're not maintaining separate diagrams. You're showing different perspectives of the same system.

Automatic propagation. Update a service in the model, every use case that includes it reflects the change.

Lightweight use cases. You're not rebuilding the architecture for each flow. Just highlighting the relevant path.

Which Use Cases to Document

Not every endpoint needs a diagram. Focus on:

User-facing journeys. Sign up, purchase, checkout. The flows users experience.

Critical business processes. Order fulfillment, payment processing, data sync. The operations that drive revenue or compliance.

Integration points. Flows that cross system boundaries. Partner APIs, webhook handlers, event chains.

Troublesome paths. The scenarios that keep breaking. If your team debugs the same flow repeatedly, document it.

A typical system has 10-20 use cases worth documenting. Not hundreds — just the ones that matter.

Making It Practical

-

Start with containers. Get the physical architecture right first.

-

List your key use cases. The 10-15 operations that matter. Name them clearly: "Create Order", "Process Refund", "Sync Inventory".

-

Trace each path. Which services are involved? What order? What data flows between them?

-

Layer on the model. Each use case becomes a view highlighting specific connections.

-

Keep them alive. When the architecture changes, use cases update automatically because they reference the same components.

Static Diagrams Rot. Models Don't.

This is the real shift: from architecture as static documentation to architecture as a living model you can explore.

Static diagrams drift from reality until nobody trusts them. A model-backed approach stays current because there's one source of truth. Views are generated, not drawn. Updates ripple through automatically.

It's the difference between a paper map and GPS. Both show the city. Only one adapts when the roads change.

The Bottom Line

C4 is a solid foundation. It describes what your system is made of.

But understanding your architecture requires both:

- Physical architecture: The containers and connections that exist

- Use cases: The paths through that architecture that accomplish real goals

Structure plus dynamics. The map plus the routes.

When you layer use cases on top of C4 — especially in a tool that treats both as first-class concepts — you get documentation that answers the questions people actually ask:

- "What do we have?" -> Container diagram

- "How does checkout work?" -> Use case overlay

- "What breaks if we change this?" -> Trace the affected flows

That's architecture documentation worth maintaining.

You Might Also Like

C4 Model Diagrams: Practical Tips for Every Level (With Examples)

Practical C4 model tips from real teams. How to create Context, Container, and Component diagrams that people actually maintain — with examples for each level and common mistakes to avoid.

C4 Model vs UML: Which Should Your Team Actually Use?

UML has 14 diagram types. Most teams use two or three. The C4 model offers a pragmatic alternative: four levels of abstraction that developers actually want to maintain.

Modeling vs Diagramming: Why the Best Teams Do Both

Pure modeling fails because nobody uses it. Pure diagramming fails because it turns into chaos. The teams that get architecture documentation right find the balance — diagram-first, model-backed.